"A farmer or stream care group, for example could take an eDNA sample to create a baseline TICI (Taxon-Independent Community Index) score before they plant up a stream or take measures to improve water quality. In time, they can then go back and resample to see any improvements like an improved TICI score and potentially see new animals that might now be present, such as native birds or species of fish that have returned."

- Waikato Regional Council Water Scientist Josh Smith

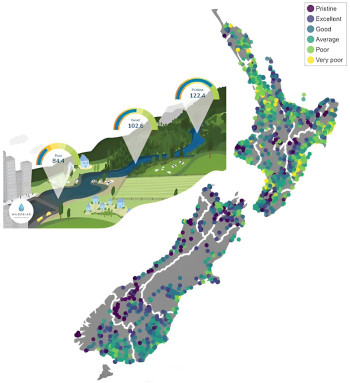

Wheel of life diagram of eDNA results from Wilderlab

What’s in a drop of water? Much more than you might expect, as it happens.

In fact, in a single drop of water, we can now find the discarded DNA of thousands of species, enabling us to map aquatic ecosystems with immense detail and precision.

It's called environmental DNA, or eDNA for short, and it refers to all the fragments of genetic material that are left behind as living things pass through the water. An eDNA analysis of a water sample will reveal the species present, and that could be anything from fungi and fish to insects and algae.

What's exciting, is that anyone can collect a sample. However, unless you're a scientist, what on earth does it all mean?

Waikato Regional Council Water Scientist Josh Smith says a new index that uses machine learning to rate the ecological health of a waterway, according to eDNA results, is a game changer.

Created by Wilderlab, in collaboration with councils across the country, it's called the Taxon-Independent Community Index, or TICI for short.

Mapped TICI scores show how the ecological health of waterways varies across the country

"While that may sound complicated, it's actually a surprisingly simple tool," says Josh, who co-authored a paper about the revolutionary index.

"TICI helps convert all that complexity into a six-tier value scale to rank aquatic ecosystem health in an accessible, intuitive and comparable way.

"This puts a lot of power in the hands of citizen scientists and the accessibility of it will help guide policy and management decisions for better environmental protection.

"Now anyone can collect a sample and understand what the results are showing in terms of ecosystem health. You don’t have to be a scientist or have specialist gear. It’s cost effective. And it enables us to build a great picture of ecosystem health both regionally and nationally to support even more strategic interventions.

"A farmer or stream care group, for example, could take an eDNA sample to create a baseline TICI score before they plant up a stream or take measures to improve water quality. In time, they can then go back and resample to see any improvements like an improved TICI score, and potentially see new animals that might now be present, such as native birds or species of fish that have returned."

Josh says a computer programme identifies the indicator species of water quality conditions, according to the Macroinvertebrate Community Index (MCI), and then looks at the eDNA information for "lookalikes".

"It's a quicker, cheaper and more comprehensive alternative to MCI – covering all life and not just animals like aquatic insects, molluscs and worms (collectively known as macroinvertebrates)."

The index is 'taxon-independent', which means the computer algorithm doesn’t need to understand what species are in the mix, it just needs to be able to compare eDNA profiles to known areas of high or low ecological health, and then categorise them based on that.

"What we find is that genetic material associated with poor stream conditions was dominated by hardier species like small aquatic worms. High scoring sequences, however, included species like mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies, which aren’t as tolerant of poor conditions.” says Josh.

"The index is also incredibly sensitive. The conditions in the immediate two kilometres upstream from the sample site were the most influential in driving site TICI scores, demonstrating the ability to detect human disturbance at a relatively localised scale.

We need faster, better ways to monitor NZ's declining river health – using environmental DNA can help."