Oliver McLeod with his volcanic map of Karioi.

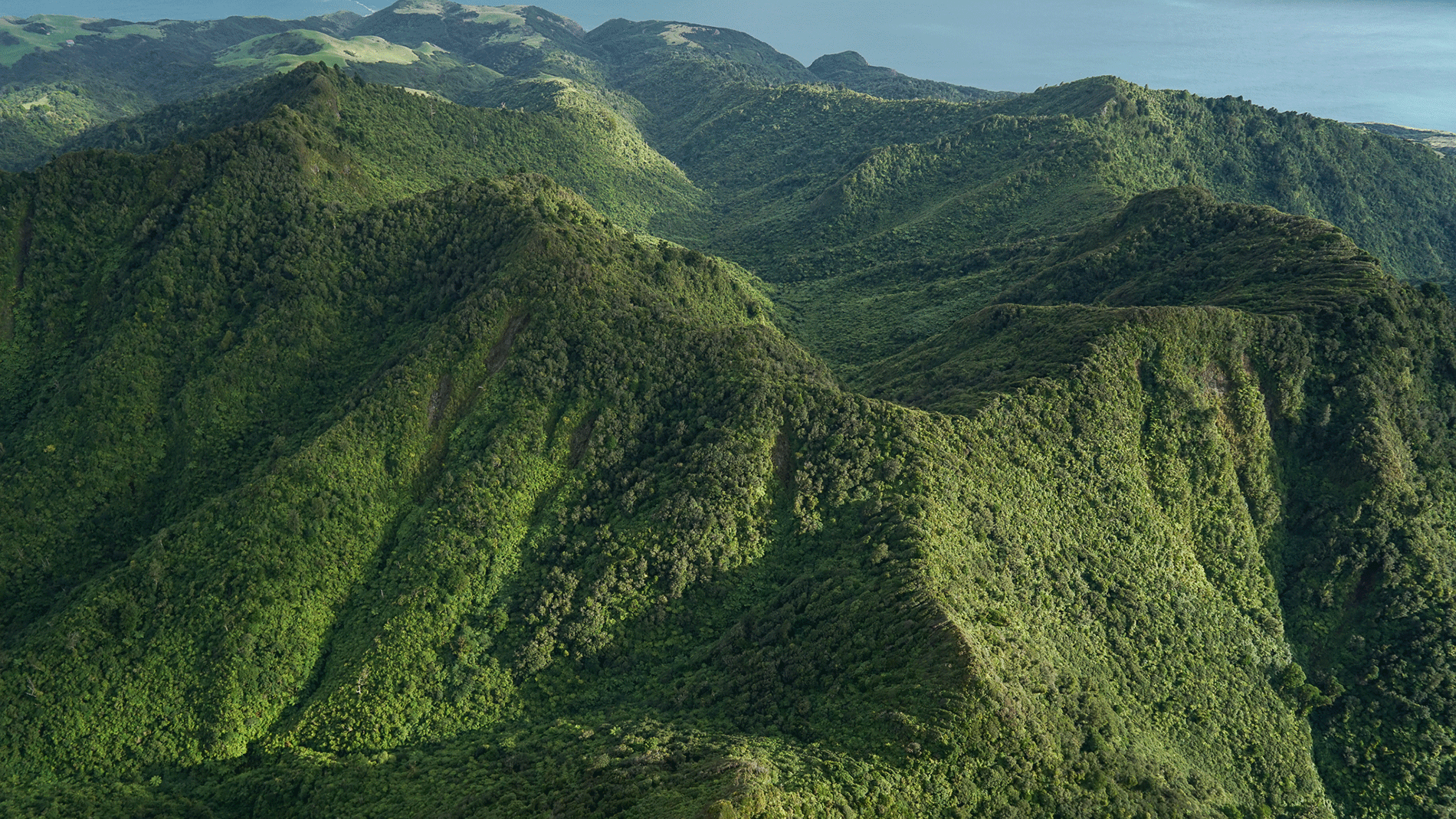

Few people would associate Raglan with volcanoes. But less than 10 kilometres southwest of the town centre sits Mt Karioi, the central figure in a rich and ancient history. Waikato Regional Council Scientist Dr Oliver McLeod traversed the maunga’s slopes, met its people and listened to their stories to produce a remarkable map that plots the geology and whakapapa of Karioi side by side.

Oliver says we owe a lot of what makes Raglan special to local volcanoes erupting between 2.6 and 2.3 million years ago. Even Raglan’s famous surf break at Whale Bay is linked to ancient lava flows which jut out from the coast and cause the waves to curl and break along the surf beach.

To find out what’s happening deep below Karioi’s surface, Oliver spent many months of 2021 and early 2022 hiking up and around the mountain armed with a backpack, hammer and GPS, collecting hundreds of rock samples, some of which were sent to Japan for testing. Geologists there determined the samples’ ages by argon dating to work out the age of Karioi’s oldest and youngest lava flows. This is the first time anyone has sampled the area in this way.

Oliver’s findings reveal a complex history of volcanic activity that lasted for around 300,000 years as eruptions produced explosive ash rings, scoria cones, lava fields and Mount Karioi itself. He says the Karioi volcanic field is one of the most complex in New Zealand because two distinct types of magma erupted in the same place. While the area features many small volcanic cones fed by deep ‘intraplate’ mantle sources (like the Auckland volcanic field), some of the lavas on Karioi itself were sourced from a shallower subduction zone (like a mini–Mt Ruapehu).

The similarities between the Karioi and Auckland volcanic fields may provide clues about future eruptions at the latter. At 756 metres high, Mt Karioi dwarfs Auckland’s largest volcano, Rangitoto Island (260m) which first erupted 600 years ago and makes up 60 per cent of all erupted material in the Auckland area. Although considered extinct, Rangitoto may share a similar fate to Karioi, which progressed from small, ash-rich cones into a volcanic shield, and finally (a few thousand years later) into a large stratovolcano like Mt Taranaki.

While scientific exploration provides a detailed geological picture, Oliver says he realised early on that studying Karioi as pure science leaves many missing pieces. The full story of Karioi is a story of whakapapa, extending from the deep geological past to the present day and into the future. Whakapapa connects people and place. It speaks of our ancestors and their kinship with the land. As such, the nature of the Karioi landscape is inseparable from the people who have lived there, past, present and future.

Oliver’s map includes reclaimed place names that have been preserved in oral history for centuries. These names don’t appear on topographical maps but were shared by kaumātua on the coast. The map also shows the locations of several ancient pā sites that when viewed in the context of the underlying strata reveal interesting links between where people lived and the specific geology that made those sites ideal for living, gardening, defending and accessing key resources.

Anyone who wants to see the map close up should look out for Oliver’s speaking tour and public talks in the second half of 2023, and his upcoming book planned for the summer.