"When it finds a host, it attaches to it with these teeth ... and they penetrate the plant so it can suck out all the water and nutrients. That’s how it feeds – so it’s like a little Dracula.”

- Kerry Bodmin, Senior Biosecurity Officer

Haustoria penetrate a host plant so the golden dodder can feed off it.

A pest plant like “a little Dracula” and found only in Waikato wetlands in New Zealand is being vanquished in shallow graves near Kopuatai Peat Dome.

Seven infestations of the fully parasitic golden dodder (Cuscuta campestris) were found in March 2024 by Department of Conservation staff who were checking a trapline on public conservation land that is managed by Waikato Regional Council as part of the Waihou-Piako flood scheme, with another an eighth infestation found during operations.

Golden dodder is an annual pest plant that depends on plant hosts for its survival. It was the first time it has been found at Kopuatai, although there are known sites at Lake Whangape, lakes Rotongaro and Rotongaroiti and Whangamarino Wetland that are being actively managed by DOC, and neighbouring properties by the regional council.

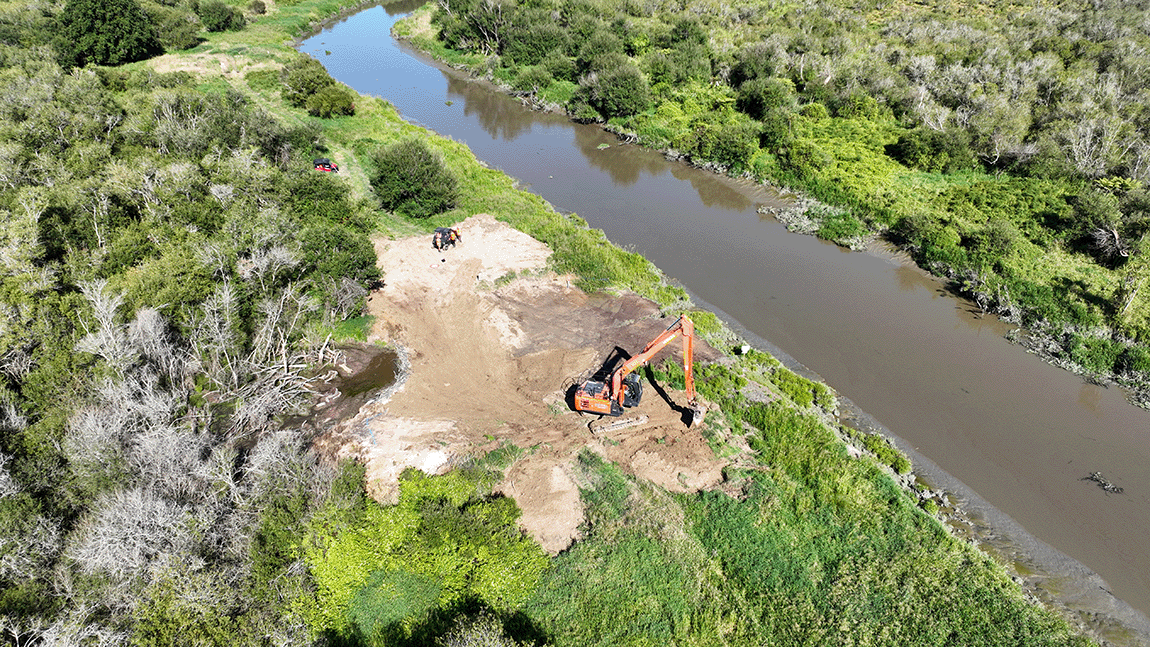

Kerry Bodmin says digging out the golden dodder infestations and burying them onsite will hopefully prevent spread.

Waikato Regional Council Senior Biosecurity Officer Kerry Bodmin says it was decided by both organisations that best way to manage the Cuscuta at the Kopuatai site was to spray it, dig it out and bury it onsite, to hopefully prevent future infestations.

Digging out the top 10 centimetres of soil would remove any seeds in the vicinity and burying the dug-up material at least 50 centimetres in the ground would prevent any seeds surviving germination.

“Hopefully we can do this once and not need to do anymore follow up control, says Kerry.

“This method is not feasible at Whangape and Whangamarino because of the size of the Cuscuta areas and the wetland environments mean we’d be more likely to lose a digger than anything else.

“At those sites, we do aerial and ground control, but we’re also trialling planting margins with native monocots that are not host species, like flaxes and sedges, with the idea that those plants will grow big enough to outcompete the seed and hosts living there.”

Golden dodder has threadlike stems that resemble spaghetti.

Golden dodder, which is toxic to stock, was first found in New Zealand in 1941 and likely arrived as a contaminant of imported crop seeds.

Kerry says Cuscuta had occurred sparsely around New Zealand in cropping, glasshouse or nursery situations, but it had never established in those environments – only in the Waikato wetlands.

“It’s actually a pretty groovy plant with so many features,” admits Kerry, who set up the golden dodder management programme when she worked for DOC in her previous role.

“When its seeds germinate, they have to find a host within 7 centimetres, or their reserves will run out. Each seedling sends out tendrils that go up and twirl around, anticlockwise, looking for something to wrap around. When it finds a host, it attaches to it with these teeth – I call them teeth but haustoria is the botanical name – and they penetrate the plant so it can suck out all the water and nutrients.

“That’s how it feeds – so it’s like a little Dracula. And that is the only way it can get its nutrients.”

Once attached to a host, Cuscuta just keeps on growing and sending out more tendrils. It parasitises on an extremely wide range of crops and weed species, and also a few native plants.

Its yellow to orange leafless and hairless threadlike stems, which resemble spaghetti, keep producing more tendrils with “teeth” to coil around host plants and penetrate their stems or leaves.

It grows rapidly into a tangle of up to five metres in two months, even smothering plants that it cannot parasitise.

Flowering occurs about 51 days after initial attachment and the first viable seeds are present at 60 days. A single plant can produce up to 16,000 seeds that are viable in the ground for up to 10 years.

Golden dodder can be spread by seed and plant fragments being moved by water, vehicles, equipment, clothing or animals. Seeds can survive the digestive tracts of birds and animals.

Kerry says if left unchecked, golden dodder would increase in abundance in the wetlands, with the potential to spread into surrounding farmlands, other wetland sites, and along access routes and waterways.

Even machinery equipment needs to be cleaned onsite before moving elsewhere.

“It’s a threat to native ecosystems in wetlands, including bittern habitat, and it’s a threat to the agricultural sector because it can reduce crop yields by 50-75 per cent. In some countries such as Africa, it is a major threat to agriculture and biodiversity, with impacts on crops contributing to economic hardship and famine.

“People are the main cause for spreading this plant to new sites. At this site there are many vectors for dispersal: this is a managed flood area and a managed wildlife reserve, so we get people coming in here for operational work who can unknowingly take it to other places.

“Our biggest challenge with this job was making sure we did not inadvertently spread the gold dodder ourselves between sites, so that meant having a clear plan, keeping ‘dirty’ gear in the contaminated zones and ‘clean’ gear outside of these sites, and making sure all gear, machinery, vehicle tyres and footwear were thoroughly cleaned on site before being used at any other location.”

To ask for help or report a problem, contact us

Tell us how we can improve the information on this page. (optional)