Coastal biology

Why we monitor coastal biology

Estuaries are an important part of our coastal marine area. They are productive ecosystems, but are also one of the most sensitive coastal areas, and are at risk from human activities. Sediment-dwelling animals (such as shellfish, crustaceans and marine worms) are important in estuaries because they cycle nutrients between the sediment and water, stabilise and rework sediments, and are an important food resource for birds, fish, and crabs. Changes in the number of species and/or the number of individual animals may point to impacts from local-scale pressures such as pollution, and broad-scale pressures such as increased sediment from land use and catchment activities.

Monitoring the sediment-dwelling animals in intertidal sand and mud flats is part of our Regional Estuary Monitoring Programme (REMP). REMP is a State of the Environment monitoring programme, and its main objective is to monitor the health of the region’s estuaries. Sediment-dwelling animals and sediment characteristics are used as indicators of estuarine health. By monitoring a number of sites we aim to build up an overall picture of the state of our region’s estuaries. Long-term monitoring is essential for detecting trends in estuarine health that may be occurring.

Results - data and trends

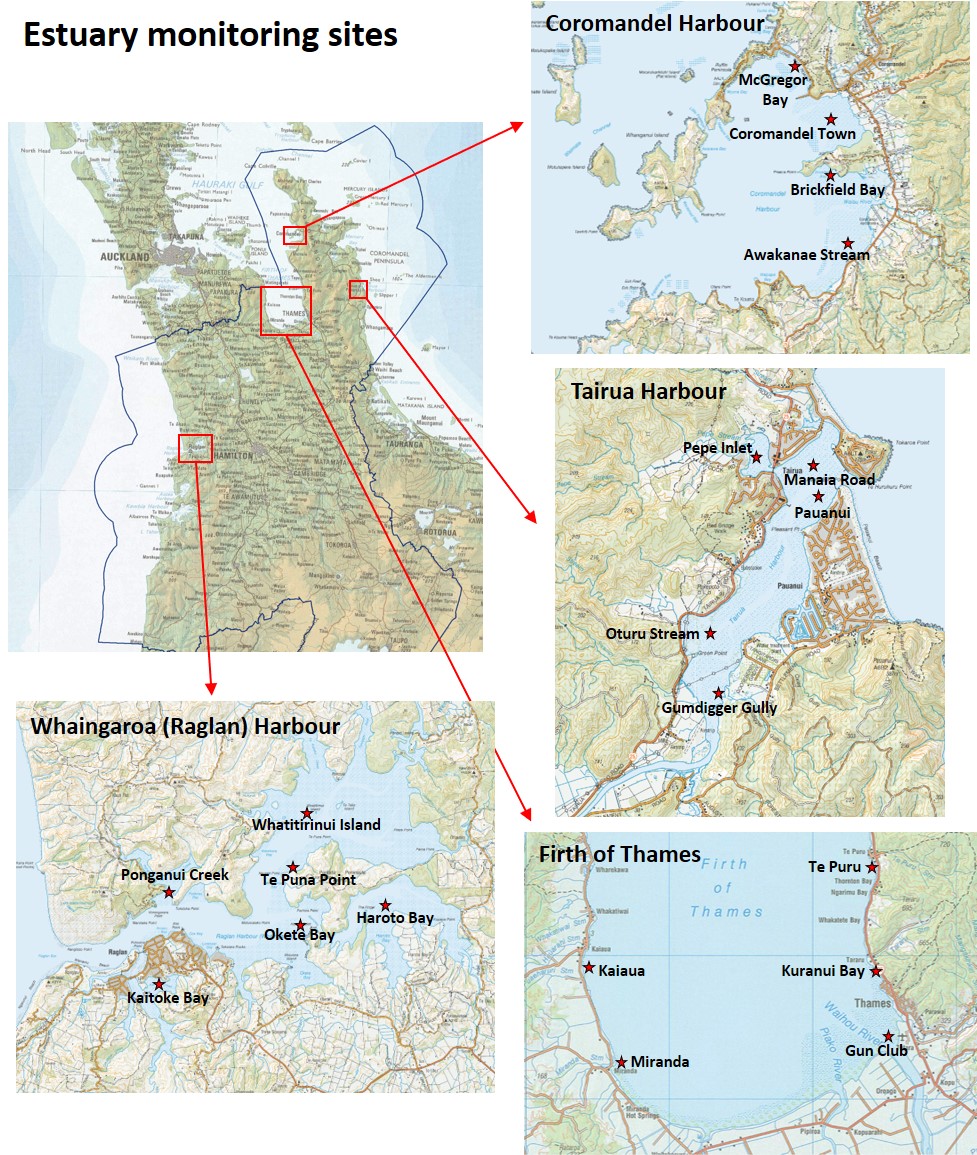

We currently monitor the sediment-dwelling animal communities in four estuaries: the southern Firth of Thames, Whāingaroa (Raglan) Harbour, Tairua Harbour, and Coromandel Harbour.

At each site we collect information on the type and number of sediment-dwelling animals present.

The animal community characteristics are summarised by a Traits Based Index that makes use of the animals’ biological traits. Biological traits are the physical and behavioural characteristics that define a particular species (e.g. body size, mobility, feeding behaviour).

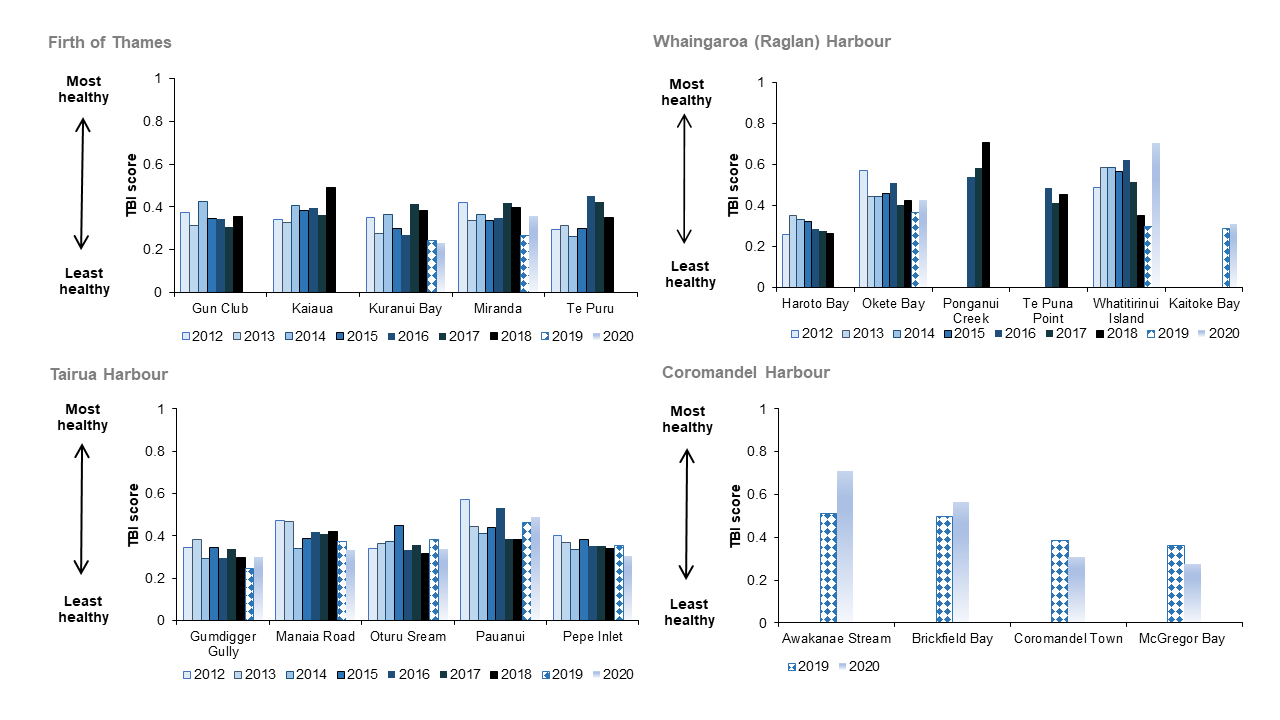

The Traits Based Index (TBI) tells us about the health of our estuaries. It ranges between zero and one, with one being most healthy and zero being least healthy. We can use the TBI to track the health of our estuary sites over time, and to compare the health of different estuaries.

This indicator shows that most of the monitored sites are moderately healthy and there were only slight changes in the TBI (and therefore in estuarine health) between 2012 and 2020.

In this indicator we report on monitoring results from 2012 onwards using an estuarine health index called the Traits Based Index (TBI). The TBI summarises animal community characteristics based on the animals’ biological traits. Biological traits are the physical and behavioural characteristics that define a particular species (e.g. body size, mobility, feeding behaviour). The TBI tells us about the health of our estuaries. It ranges between zero and one, with one being most healthy and zero being least healthy. We can use the TBI to track the health of our estuary sites over time, and to compare the health of different estuaries.

Comparison of Firth of Thames, Whāingaroa, Tairua and Coromandel Harbour

Comparison of the four estuaries shows:

- Many of the sites are moderately healthy (having a TBI score between 0.3 and 0.4), some are in poor health (having a TBI score less than 0.3), and some are in relatively good health (having a TBI score greater than 0.4).

- Only Kuranui Bay and Miranda were sampled in 2020. These were both similar to previous TBI results and indicate that sites in the Firth of Thames are broadly similar to one another in terms of estuarine health.

- There was much greater difference between sites in Whāingaroa (Raglan) Harbour, when compared to the differences between sites in other estuaries. Haroto Bay and Kaitoke Bay were the least healthy, whereas Ponganui Creek was the healthiest. Whatitirinui Island TBI score increased from the previous year, returning to the level observed in 2016.

- There were differences between sites in Tairua Harbour, with Pauanui having slightly higher TBI scores (indicating a healthier environment) than those at Pepe Inlet, Gumdigger Gully and Oturu Stream.

- Four sites were sampled for the first time in Coromandel Harbour in 2019; sites in the northern part of the harbour (McGregor Bay and Coromandel Town) were moderately healthy, whereas sites in the southern part of the harbour (Brickfield Bay and Awakanae Stream) were in relatively good health. Results from 2020 were similar to the previous year.

- At most sites, there were only slight changes in the TBI, and therefore in estuarine health, between 2012 and 2020. We expect the TBI score to vary slightly from year-to-year due to natural variability. There is not yet enough data to analyse trends statistically.

The graphs below show the TBI score for each monitoring site in the three currently monitored estuaries for 2012 to 2020. A full-size image is also available on this page for you to view or download.

The Excel data file below contains the source data for this indicator's information.